Optimal Betting

Parimutuel betting

Parimutuel betting is a system in which all bets of a particular type are collect together in a pool. The payout is rewarded by sharing the pool among all winning bets. This differs from fixed-odds betting in that the payout amount is not determined until the pool closes.

A fraction of all bets placed are removed by the house. This quantity is called the takeout and differs by market. Takeout values between 5% and 30% are typical.

Formalism

Suppose there are $n$ runners in a race each with amount $\{a_i\}_{i=1}^n$ invested on them. For each dollar invested on runner $i=1,\dots,n$ the payout should that runner win would be

where $T \in [0,1)$ is the takeout. There are more complicated bet types like trifectas, but for simplicity we focus on the the win case.

The division of funds among the various runners determines what the market thinks the probability of each runner winning is. That is the market thinks that the probability of runner $i$ winning is $1 / a_i$. If one is able to determine the true probabilities better than the market can there is an opportunity.

If the true probability $p_i$ of runner $i$ winning is greater than what the market believes it to be then betting on runner $i$ is likely to be successful (ignoring the takeout). If this happens we say that runner $i$ is an ‘over’.

Given bets $x \in [0, \infty)^n$ the expected profit is thus

since the total investment on runner $i$ will be diluted to $a_i + x_i$ by betting and $\sum_{j} x_j$ is the cost of placing such bets.

Constrained nonlinear optimisation

Clearly, we have a function $f$ to maximise. We are constrained by the fact that in parimutuel betting one can only buy bets and not sell them. We thus have $n$ constraints,

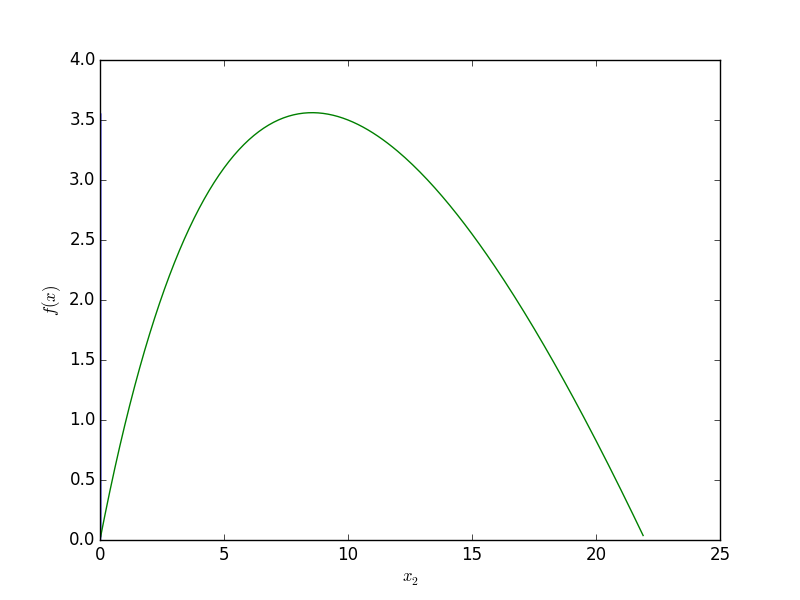

Consider an example where there are two runners and runner 1 is large favourite to win $p = (0.7, 0.3)$ and the public agree $a = (100, 15)$, and suppose the takeout is modest $T = 0.10$. We can exploit the fact that the public has not invested enough on runner 2.

By investing \$10 we expect to make a profit of around \$3.50.

Example: gradient descent

In general, the problem is to choose $x$ such that $f(x)$ is maximised. The simplest way to solve this optimisation problem is with the gradient descent method. We start at $x^0 = 0$ and compute $x^{i+1} := x^i - \lambda \nabla f (x^i)$ until $f(x^i)$ and $f(x^{i+1})$ are close. Any time we fall outside the allowed region we project back onto it.